Death to Scott Thompson, Long Live Buddy Cole

It feels fitting to leave Thompson behind in the graveyard he made for Cole to vamp in. The evil that men do live after them, the good is oft interred with their bones. So let it be with Scott Thompson’s comedy career.

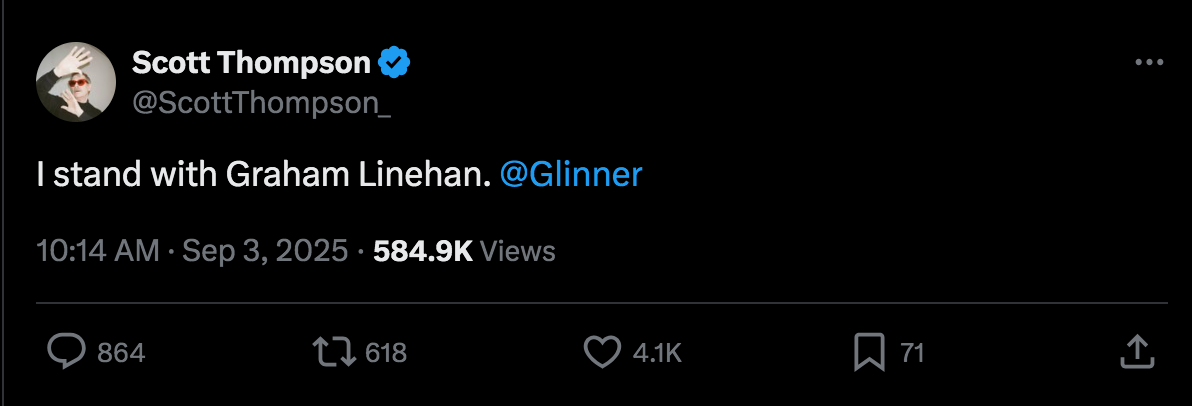

Friends, comedy fans, and running faggots: I come not to praise Scott Thompson, but to bury him. These days every trans person is bracing themselves for the moment a childhood hero publicly betrays them. I got my chance when Thompson decided he needed to stick up for Graham Linehan.

In case you’re unfamiliar with what TERFs are up to overseas, Linehan is a washed-up comedy writer who is such a militant freak about hating trans people that his wife literally left him over it. He recently was arrested in Britain for the crime of publicly harassing and threatening a teenage girl. Because evidence used to validate her legal claims of harassment appeared on Twitter, some weirdos think that his arrest is a free speech issue.

It’s actually just a small part of a decade-long spittle-faced tantrum Linehan has been holding ever since some trans people told him that he wrote a shitty episode of The IT Crowd. Regardless of the pathetic nature of this beef, TERFs have positioned Linehan as a champion of free speech instead of a creepy, insecure boomer dork who is bullying children to preserve his fading relevance.

And Scott Thompson is now one of Linehan’s defenders, which sucks big-time for me as a transmasculine comedian and long-time fan.

Thompson was one of the first transgressive queer comedians I encountered, thanks to Comedy Central’s mid-90s reliance on syndicated Kids in the Hall reruns to fill their scheduling gaps. I would run home from school and sneak down to the basement and turn the TV on, riveted by the mix of cruel anarchist absurdity that the Kids always provided. Every episode provided twenty minutes of hysterically funny discomfort, a tonal mishmash that could include a song about terriers or a monologue about an abusive father. They felt like a smarter, meaner version of Saturday Night Live, with a comforting roster of repeating characters and catchphrases that camouflaged something radical.

It felt punk and cool, and because Scott Thompson was there, it was queer too.

It would be hard for me to overstate how important Scott Thompson is to me as a gay dude who loves comedy, even if I didn’t necessarily know I was a gay dude when I was watching his work. There were plenty of jokes about gay dudes in that early alt comedy scene, but they were mostly made by straight male comedians who could think of nothing funnier than the idea of blowing each other. Queer comedy that was actually made from a queer perspective was hard to come by, especially for a kid growing up in Ohio.

The queer sketches in Kids in The Hall felt vital and forbidden, like a portal into a secret world. One of the truly remarkable things about the queer sketches in Kids in the Hall is that they capture everyday life for queer people in the 80s and 90s in a way that more sanitized media cannot. Gay people in KITH sketches were sometimes called slurs, and beaten and harassed by bigots in the course of their daily lives. When they weren’t getting the shit kicked out of them, they still struggled to get laid and pay the rent. If these characters were entirely created and portrayed by straight comedians it would have been unbearable, but Thompson’s influence behind the camera kept them somewhat authentic.

One of my favorite recurring gay bits on KITH is the Steps sketches, where we get to watch a trio of queer archetypes hanging out and talking shit on the steps outside their favorite coffee house. As an adult, my curiosity about these sketches compelled me to visit the Church Street neighborhood that they took place in and learn about the deep importance of that particular set of steps as a place for queer folks to gather and be visible in Toronto. (If you’re a Chicagoan, the Belmont rocks served a similar purpose.)

Visiting that neighborhood was a huge deal to me as a newly out adult. It was one of the first times I felt a real personal connection with queer history, one I'd learned about without even realizing it. I never would have thought to find the spot if I hadn't imprinted on the Steps sketches as an impressionable teenaged egg.

Another one of my favorite Kids sketches is this bike harassment sketch. In it, Thompson deals with a bully who won’t stop pedaling by his porch every morning and calling him a fag. He resolves this problem by putting on a bear outfit, ambushing the bully, and clawing his face off.

I remember seeing that sketch on a day my coat had been stolen from my locker and stuffed in a gutter near the school. I’d spent several hours wandering around looking for it, and it was dark and cold by the time I finally got home. I made myself some soup for dinner and huddled under a blanket in front of the TV, and watching Scott Thompson murder a bully was the first time I felt good all day.

And I didn’t even know I was a faggot yet! How’s that for the power of queer art?

The most iconic Scott Thompson creation is Buddy Cole. If you’ve ever even casually interacted with the oeuvre of the Kids, you’ve met Buddy once or twice; an effete needle-toothed pixie of a man with a permanent cig between his long thin figures, dressed like a lazy Halloween Liberace and lisping so hard he’s practically daring you to call him a slur.

Nobody bullied Buddy Cole, and that’s why he was a hero of mine even before I knew we had so much in common. What I did not know then was that Buddy was based on a real person that Thompson knew, briefly and bitterly, until AIDS took yet another lover off of his speed dial. Thompson only dated/loved/fucked the guy for a few weeks, but that was enough to make a lasting impression:

“But it came from a very simple thing. I fell in love with a guy who was very much like Buddy, a very effeminate man who had a wicked wit. And at the time I was so surprised because I had so many hang ups about my masculinity and all of that stuff so I was quite amazed that I would fall for someone that was so effeminate because his queeniness was so powerful, he owned it, he didn't back down from anyone.”

It is a sad irony that a gender non-conforming dude launched the career of a comedian who mocks gender non-conforming dudes like myself. One would hope that someone who lauds himself as a take-no-prisoners social critic would see that irony, but Thompson appears to be immune to that kind of introspection when it comes to himself or his career. Take this snippet from a post-cancer interview with Thompson, where he deadnames and mocks a trans dude that takes the same gender-affirming medication that he does:

“I talk a lot about the side effects of chemo – like when I grew breasts! Suddenly I'm talking about cancer and hormones and transgenderism, and what could be more topical? I had bigger tits than Chastity… I mean, Chaz! (Laughs)

I've been thinking a lot about this, the whole transgender thing. When I had cancer the chemo converted my testosterone to estrogen, I grew little tits like Jodie Foster in "Taxi Driver," I became very emotional, I became obsessed with "Twilight," I lost my ambition and my sex drive. I'm thinking, ‘But that doesn't make me a woman; I'm just a man with a hormonal imbalance.’[...]And now I'm back, because I went through testosterone therapy.”

As a human being, Thompson has been through a lot of pain and tragedy. Because of the way our culture has collectively glossed over the tragedy of the AIDS epidemic, it’s easy to forget how absolutely terrifying it was to be a gay dude in the 80s. Thompson decided to come out and be his authentic self on that Second City stage in part because he thought it didn’t matter, because he assumed he was likely to die. A lot of queer folks lived through that apocalypse and came out with the trauma-induced battle damage one would expect. His anger makes sense, and the person behind the persona deserves our empathy.

But that empathy ends at the edge of the stage Thompson stands on, and he is responsible for what he says there. As a trans person, I am tired of making polite excuses for the assholes that inspired me. I wrote this because I feel I have the right to make this critique as a peer of Scott Thompson, not a fan. He is a big part of why I am now a gay man who makes a career out of telling gross jokes to amuse myself and briefly evade my own nihilism. He's the one who taught me to claim this space and defend it, and so I will.

I also write this knowing that Thompson would most likely refuse to recognize me as a gay male peer, no matter what I said or did. Trans people do not owe kindness or patience to people who have repeatedly failed to extend it towards us.

So, enough from that guy. The time has come to separate the art from the artist entirely, and see what value remains. To be honest, a lot of the Buddy Cole material didn’t age well. This early monologue is a great example of why. It’s pretty much just a list of stereotypes about other cultural groups, framed from a white gay male perspective and punctuated with a laugh track.

The jokes felt cutting and smart to my teenage self— there’s Cole, telling it like it is to other racist white gays! — but my adult self cringes at every ironic slur. Thompson has always been a white gay guy who tells jokes for other white gay guys. It’s no surprise to me that he misgendered Chaz Bono and made fun of him for having tits, because that’s the limitation of his schtick. When he tries to turn the lens on any other population, his once-incisive gags feel especially stilted and underwritten.

But there is something of value to be found in Thompson’s work when one considers it as a furious rejection of assimilation in favor of the uniquely liberating ethos of transgressive queerness. The best parts of Buddy Cole are still there, for anyone who needs them; his anger, his wit, and his steadfast unwillingness to cede a single fucking inch to the people who hate his faggoty guts.

My favorite Buddy Cole monologue is one of the last ones, where we find him swanning around a styrofoam graveyard and mourning a dead slutty friend. Cole tells us the story of this dead man’s life, joking about his involvement in the leather scene and his refusal to pander to shocked straight folks. Cole’s best line of the sketch also serves as its thesis: “We both believe that respectability is for five-star hotels, not people. Though, you will find me in the Michelin guide.”

It’s a bittersweet and funny sketch, and it ends on a great moment: Cole draped across a gravestone like Norma Desmond, rolling his eyes and groaning in sardonic agony to the ghost of his long-dead partner in hedonism:

“Maybe it’s better this way. I don’t think you could handle what’s going on now. Get this: fags are becoming respectable.”

I could not come up with a better epitaph than that. Because whether Scott Thompson likes it or not, I’m one of the fags that loved his work back in the day. And I’m also disgusted by fags debasing themselves by trying to become respectable, especially when it’s an old bitter queen like Scott. He can cry about being censored by the left all he likes, but that’s a meaningless stance when you’re carrying water for the Trump administration. There’s only one faggot in this conversation who agrees with the President of the United States, and it sure as hell ain’t me.

It feels fitting to leave Thompson behind in the graveyard he made for Cole to vamp in. The evil that men do live after them, the good is oft interred with their bones. So let it be with Scott Thompson’s comedy career. Lay this tired, angry man to rest and let the depraved ghost of his works roam the earth, haunting the earthly stage and making space for newer and more insightful voices like Nori Reed, River Butcher, Patti Harrison and Mae Martin. Death to Scott Thompson, and long live Buddy Cole.